“Censorship, especially of school libraries, always presents itself as saving children from harm, but in fact it introduces new sources of harm,” said Ira Wells, author of On Book Banning, in an interview over email. “It harms children by depriving them of information or narratives that may have enriched their lives. It harms them by teaching them that, when they encounter an idea that they find difficult, the solution is to censor, to silence, or cancel — which is a deeply undemocratic idea.”

Books have always been our most powerful teachers, not just of knowledge but of empathy. They let us live vicariously through people who love, believe and experience the world differently than we do. They can comfort, unsettle or open our eyes.

From fiction to non-fiction, they challenge our interpretation of the world and remind us that other people’s stories are how we learn to understand one another.

Across the country, this tool is under attack.

As Wells detailed in his book, examples of censorship span every era, from Roman emperors burning books to school districts today pulling titles from shelves.

In 2024, Washington state passed HB 2331, a law meant to prevent schools from banning books on the basis of addressing or representing marginalized voices. It limits who can challenge materials to parents or guardians and requires each complaint to go through an open review process, in an effort to ensure fear or ideology doesn’t decide which stories people get to read.

That being said, Washington hasn’t escaped the effects of book bans and challenges. The national debate over what information is appropriate and who should have access to it still finds its way into our local discourse.

In July, the League of Women Voters of Bellingham/Whatcom County book group gathered to discuss their most recent reads: a collection of banned books. Each person chose one title from the recent Banned Books lists and came together to talk about what those stories revealed.

“Everybody reported favorably on having been glad that they read that book,” said Annette Holcomb, a member of the book group. “A couple of people who had chosen to read 1984 ... found it very difficult to read.”

Donna Meehan, another member, agreed that fear is often at the center of book bans.

“It makes people uncomfortable,” Meehan said. “(Reading banned books) makes them have to reevaluate their own feelings and emotions that they’re not ready to do.”

They said that while the conversation around book banning isn’t as visible in Whatcom County as in other parts of the country, the issue is still relevant.

“It is still a big issue, and it can impact our whole lives,” Meehan said. “People, for instance, ... if they’re not getting the right history information, they’re voting without the proper information.”

PEN America, a nonprofit organization working to protect free expression that tracks censorship across the U.S., defines school book banning as a form of censorship: any action that removes or restricts student access to a book based on its content and community objections.

As mentioned in Wells’ book, when governments have outlawed stories they deemed obscene, historically, curiosity always intensified people's desire to know what was being hidden.

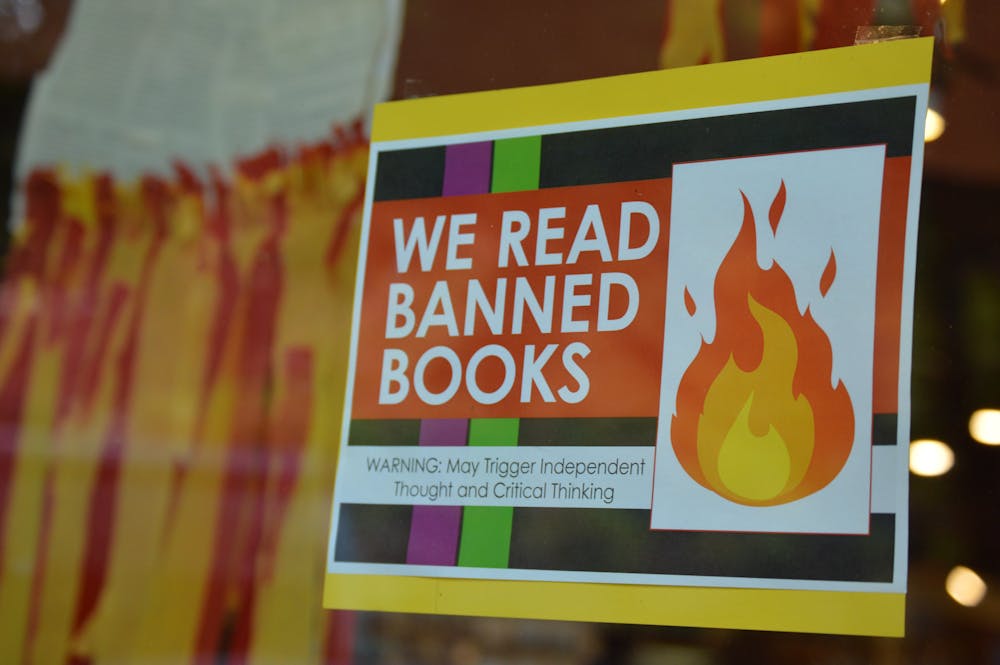

Kelly Evert, co-owner of Village Books and Paper Dreams, has seen this outcome firsthand.

“The next generation will hear that the book is banned, and they’ll question why, and then they’ll come in and get it,” Evert said.

As these debates continue again and again, both academic and public libraries remain on the front lines of the discourse.

“Academic libraries are evidential. What that means is that we keep the evidence for ... all the different kinds of fields that we have – it's very important to have a broad spectrum of representation,” said Sylvia Tag, Western’s Children’s and Young Adult Literature Librarian.

“The library having a material that someone objects to doesn’t mean that the library is condoning any particular viewpoint,” continued Tag. “That’s not what knowledge acquisition is – it’s availability.”

Tag explained that Western’s goal is to preserve information and foster understanding.

“Anytime anyone has a question about a material, we’re ready to have a conversation... we take it very seriously,” Tag said. “There could be a response of, if you object to this book, could we purchase a book that has another viewpoint, so that the representation could be more balanced.”

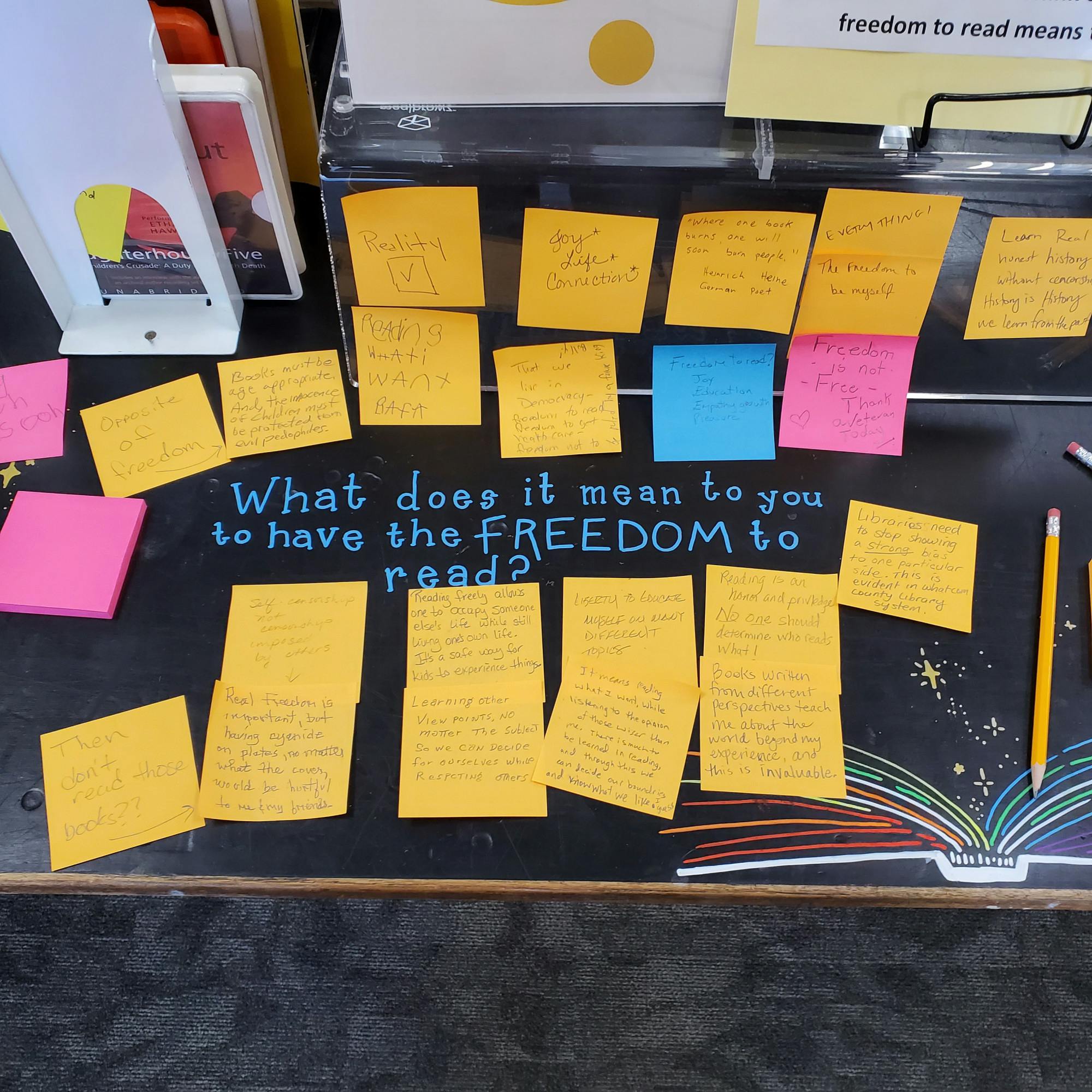

Like Western, the Whatcom County Library System prioritizes comprehensive access over restriction.

“We don't really talk about book bans,” said Lisa Gresham, Collection Services Manager for the WCLS. “What we talk about is intellectual freedom.”

“Since I’ve been here, that action has never been we’re going to remove the book from the library,” Gresham said, as the library just reclassifies books, when necessary, for a different audience.

Gresham said every WCLS staff member, from custodians to directors, goes through training on how to talk about intellectual freedom and censorship.

“I'll tell you, 9 times out of 10, people say, ‘Oh, I didn't think about it like that. You have a really hard job serving all of those diverse interests. I still don't like the fact that this book is here, but now I understand why it is, and I can live with that,’” Gresham said.

"The library is for everyone,” Gresham said. She said the library aims to balance a range of perspectives while ensuring everyone is treated with equal importance.

Moms for Liberty, a national parental rights group with chapters in dozens of states, is lobbying for book bans across the country.

Moms for Liberty says restricting school access to certain books isn’t book banning. “No books are being banned ... Write the book, print the book, publish the book, put the book in a public library, sell the book. We’re talking about a public-school library,” said Moms for Liberty co-founder Tiffany Justice, in an interview on The ReidOut.

According to the research of PEN America, the vast majority of challenged books “predominantly targets books about race and racism or books featuring individuals of color and LGBTQ+ people and topics, as well those for older readers that have sexual references or discuss sexual violence.”

So, while advocates of book banning and censorship say that restricting access to certain materials is a matter of protecting parental rights, the books being challenged often mirror long-standing efforts to suppress marginalized voices.

“I find it’s hard to shelter your child from everything that’s in the world,” Meehan said. “You have to be open to discussing it.”

As Ira Wells writes, every generation faces the same temptation to believe it can silence what it fears. However, history shows that erasure never works – it only deepens the need to remember.

Janessa Bates (she/her) is a city news writer for The Front this fall quarter. She is currently studying visual journalism and political science at Western. Outside of the newsroom, she co-leads a club called WWU Photo Video Club, enjoys reading and loves to picnic with her dachshund. You can reach her at janessa.thefront@gmail.com.