Depending on the time of year, you’re bound to see some type of salmon running up a Washington waterway—spring steelhead, summer sockeye, fall chinook, chum, coho or the year-round cutthroat. But in many places, that journey ends abruptly at a culvert: A narrow, aging pipe where roads cross streams, often blocking fish from reaching their historic spawning grounds.

"A single bad culvert can cut off tens, hundreds of miles of stream habitat and make them unusable for fish,” said James Helfield, an ecology professor at Western Washington University.

A view of Lake Creek culvert with large woody debris blocking the waterway on the northbound side of I-5 in Whatcom County, Wash., on May 6, 2025. This culvert is located just south of the North Lake Samish exit 246 and is set to be replaced with a fish passage this summer. // Photo by Josh Maritz

Sweeping statewide efforts aim to change that. The Washington State Department of Transportation is removing 17 outdated culverts and replacing them with 10 fish-friendly structures along a six-mile stretch of Interstate 5 through Whatcom and Skagit counties.

Construction on the project began in April 2025 and will restore nearly five miles of salmon habitat, allowing fish to swim freely beneath I-5 and nearby roads.

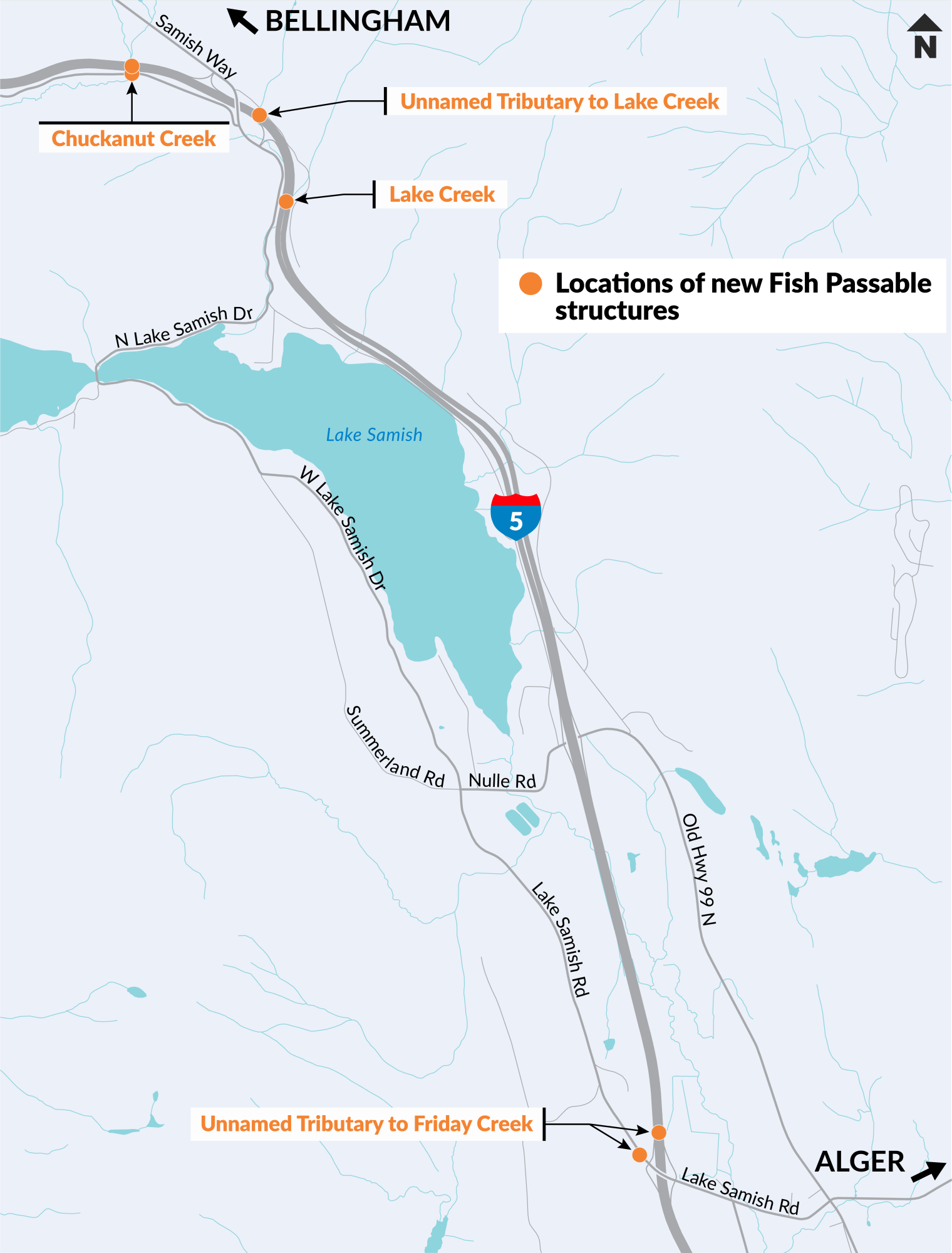

This multi-year project will reconnect natural stream habitats near Lake Samish for Lake Creek, Chuckanut Creek and unnamed tributaries to Friday Creek and Lake Creek along a stretch of I-5 between Chuckanut Creek (milepost 247) and Lake Samish road (milepost 240).

A graphic map of fish passage construction on I-5 in Whatcom and Skagit Counties. Orange dots show the locations of new fish passable structures. // Photo courtesy of Washington State Department of Transportation

“Culverts can block fish from swimming upstream. The noise and flow through the metal pipe can scare them off, but the bigger issue is usually size,” Helfield explained. “Undersized culverts concentrate water flow, acting as a fire hose, which can cause blockages, washouts or streambed erosion. This often leads to ‘perching,’ where the culvert ends up hanging above the stream, making it impossible for salmon to enter.”

The first phase of construction began on April 30, 2025. Crews are currently working on constructing a bypass road at night from 8 p.m.-5 a.m. to minimize disruptions for drivers. The project will be completed in three phases that end winter 2028, barring any setbacks.

While the timeline may seem lengthy, experts emphasize the long-term benefits of the project far outweigh the short-term inconvenience.

“When you think about the lifespan of these projects and this infrastructure being in the ground and functioning appropriately for the next 80 to 100 years. (Three) to seven years to get a crossing in place is not that big an impact,” said Joel Ingram, a fish passage scoping biologist for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The wildlife agency plays a crucial role in planning and implementing fish passage projects, which are then implemented by the state transportation agency, who often contract private crews.

Kiewit, a construction and engineering company, is heading the project. They've been awarded numerous contracts to remove fish barriers and create fish-friendly habitats statewide.

This statewide construction is due to a 2013 injunction the U.S. District Court issued requiring the state to accelerate barrier correction on salmon and steelhead streams west of the Cascade Mountains and north of the Willapa and Columbia River drainages and replace the majority of them by 2030.

This injunction reaffirmed a 1974 court ruling known as the Boldt Decision, which recognized tribal sovereignty and established tribes as co-managers of fisheries alongside the state.

The new crossings will provide stream habitat gain of nearly five miles, which supports populations of salmon, steelhead, other aquatic species and wildlife, according to WSDOT.

The project cost nearly $160 million. Funding is provided by the Federal American Rescue Plan Act and the State Move Ahead Washington funds. The average cost to replace a culvert statewide is $20 million, according to NPR.

Planning for the I-5 fish passage project near Lake Samish began in 2021. The initial phase involved hydraulic assessments to analyze stream conditions. In partnership with Tribal partners and permitting agencies, WSDOT assessed the needs of each stream crossing to allow natural fish movement and determined the appropriate structures, Megan Mosebar, the department’s project engineer, said in an email.

"These are stream crossings designed to be safe under all conditions that we're likely to see during the design lifespan of these crossings," Ingram said.

Once the bypass roadways are built and traffic is moved over, Kiewit will begin work during the day in the closed portions of the roadway. Part of the reason fish passage construction is in the summer months has to do with the “fish window,” said Mosebar.

The "fish window" is timed to ensure in-stream construction happens when salmon are least vulnerable, minimizing harm to the species. This period, typically from mid-July to mid-September, avoids key stages of the salmon life cycle—such as fall spawning, winter egg development and spring juvenile migration—and takes advantage of lower, more manageable summer water flows, Ingram explained.

For updates on the project, visit WSDOT’s website.

Statewide, there are 4,037 highway crossings on fish-bearing waters. Of those, almost half are documented fish passage barriers. Of these, 38% block a significant amount of upstream habitat, according to a fish passage report by the state transportation agency.

WSDOT currently bases fish passage project priorities on eight key factors but is in the process of creating a new prioritization system with state wildlife regulators.

As of June 1, 2024, WSDOT has corrected 146 injunction barrier culverts and restored access to 571.18 miles of potential habitat for salmon and steelhead. To date, the department has completed 420 fish passage barrier corrections across the state.

Locally, the City of Bellingham has proposed three projects for the future on Padden and Baker Creek. The city has completed 20 structures to improve fish passage, the most notable being the Middle Fork Nooksack River and the I-5 Padden Creek crossings.

An overhead view of a Padden Creek fish passage bridge under 33rd St., adjacent to I-5, in Bellingham, Wash., on May 9, 2025. This fish passage was a part of the I-5 Padden Creek passages, being completed in 2022. // Photo by Josh Maritz

In Whatcom County, Devin Soliday leads restoration crews with the Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association each summer to remove culverts so salmon can return to their ancestral routes.

“When we're doing our pre-assessments, we see schools of fish that can't get any farther,” Soliday said. "To be able to watch a culvert get removed and a bridge be built, and then do post assessments and see fish above where that barrier was. That's pretty amazing.”

Rose Anne Featherston lives in Everson, Wash. on the Goodwin Creek tributary. In 2016, the salmon recovery nonprofit helped build a fish-friendly passage on her property, along with two of her neighbors' culverts. The project was free of charge with the help of a Whatcom Conservation District grant.

"There were fish in the creek within days (after removing the culvert). It was unbelievable," Anne Featherston exclaimed. "The inconvenience of the construction was well worth the end product, which is paying homage to the beauty of where we live and making the waterway function."

A sockeye salmon swimming in Goodwin Creek near Rose Anne Featherston’s property in Everson, Wash, in 2016. Anne Featherston had a culvert removed, which allowed salmon to move further upstream in her property. // Photo courtesy of Rose Anne Featherston

Anne Featherston now serves as the president of the board of directors at NSEA, all thanks to that project.

“It's really cool to fit in that niche of being great for the fish and the habitat, and then also make the landowner happy and give them improved access," Soliday said.

This year, NSEA’s funding was paused due to significant federal funding cuts.

In contrast, Washington lawmakers approved $1.1B for salmon habitat restoration on May 5, 2025, which brought WSDOT’s program roughly two decades total to $5.2 billion.

Anne Featherston views the state's efforts as essential amid increasing strain on local resources.

"I think (removing fish barriers) is necessary. We’ve got to work for maintaining that, and it's hard because we have a lot of people coming into the area, meaning fewer resources," Featherston said.

Ingram echoed that sentiment, emphasizing the long-term consequences of neglecting ecological considerations in urban planning.

"We have developed Western Washington over the last 100 to 120 years without consideration for natural processes and what our infrastructure does to stream channels and the associated biological species," Ingram said. “We have an obligation as a state and country to the sovereign Native American tribes that settled here.”

Together, these local projects and state investments reflect a unified commitment to restoring salmon runs and honoring ecological and cultural responsibilities across Washington.

"Here in the Northwest, I think we can all agree salmon are an essential resource economically, culturally and spiritually. They're an iconic species that has been a cornerstone of civilization in this part of the world for a millennium," Helfield said. "If it means a little bit of traffic headaches, well, I think that's a sacrifice to make.”

Overhead view of the Unnamed Tributary to Lake Creek culvert on the northbound side of I-5 in Whatcom County, Wash., on May 6, 2025. This culvert is located at milepost 246.2 and is set to be removed in summer 2027. // Photo by Josh Maritz

Josh Maritz (he/him) is a city news reporter for The Front this quarter. He is a third-year environmental journalism student at Western with a minor in economics. In his free time, he enjoys going for long trail runs and listening to '90s grunge. You can reach him at joshmaritz.thefront@gmail.com.