Off Mount Baker Highway in Glacier is a skatepark called the Coal Pad DIY. What was originally a concrete slab for a coal deposit in the 1940s has since blossomed into a full-blown skatepark, built by Glacier skateboarders and snowboarders.

As the town started to get more populated with snowboarders and families moving there, locals started building jumps for their dirt bikes and mountain bikes. Eventually, enough of the coal got groomed off the concrete slab and people began to skate it.

However, it wasn’t until the early 2000s that it started to get developed into a DIY skatepark.

“People got inspired because Orcas Island Skatepark was getting built, and it was one of the first big skatepark projects in Washington state,” said Ryan Davis, the Northwest representative of Mervin Manufacturing and president of Glacier Skate Association.

Driven mostly by snowboarders, the Coal Pad was built so they had a place to skate during the spring and summer when the rain had stopped.

“Jeremy Miller did multiple fundraisers and tried to get things rallying there,” Davis said. “They're just raising like $200 to $300 to $500 at a time, getting concrete bags, hand mixing it and learning as they go.”

The land was then sold in an auction in 2009 to Joe King, who had never seen the land before.

“He showed up on the land and realized that there's people building jumps and skate features on his land,” Davis explained. “At first he kind of put a kibosh on it, and was like, ‘No.’ I don't think he wanted to deal with the liability.”

Faced with all of their hard work and dedication being torn down, the community in Glacier rallied and sat with King to explain their dream of what they wanted to build. King relented but on the conditions that they absolve him from liability and get a permit. Unfortunately, due to the costs of having all of this work done to save the park, energy fizzled away, leaving only a small group of people dedicated to keeping it alive.

In the winter of 2014, Mt. Baker Ski Area had seen the lowest amount of snowfall in about 25 years, forcing the ski area to cancel their Legendary Banked Slalom, where riders race down a winding course with banked turns. Because of the cancellation, hundreds of people who had traveled to Glacier for lodging during the slalom found themselves with nothing to do. This is when the community rallied together to get the fundraising needed to secure the Coal Pad.

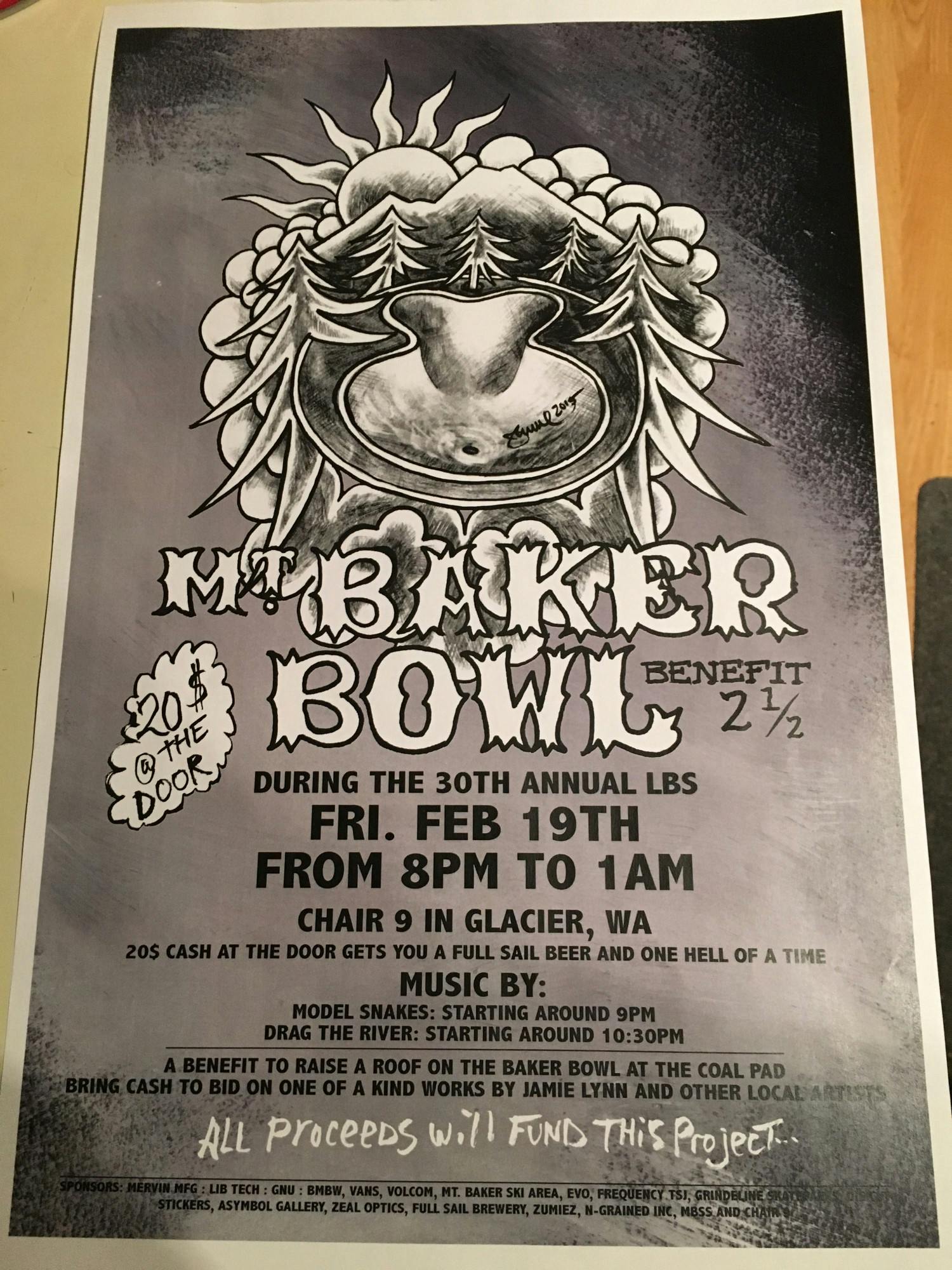

“So many people were inspired and wanted to contribute in some way,” Davis explained. “Jamie Lynn donated like 10 of his original paintings. The Cook family opened the doors at Chair 9, and we charged $20 a head. I'd seen this band that I was super pumped about in Seattle, and I messaged and asked them if they would play the Coal Pad benefit, and they agreed.”

It paid off in the end. That night they raised $26,000, which Davis said was unheard of for a DIY skatepark. Davis noted that it was the community that pulled together to support the project.

After that, building began and was underway. But King had heard about the construction going on and wanted to sit down with Davis and his friend, Joe Lauderdale, to discuss what was happening on his land.

“We walked up the road with him and gave him the five-minute elevator speech about the passion of it and how people in Glacier don't have a place to skateboard because no one has concrete,” Davis said.

But what sold King was this small tile part of the skatepark that was done by Cummins, Lynn and Red.

Cummins made the tile in his studio and brought Lynn down to help. It took them about two weeks to make—all by hand—and they painted every piece themselves. Installing it was a challenge, too, as when you pour a bowl and want to plan for a tile ribbon around it, you have to notch it carefully, which isn’t easy to do, Davis explained. Red had heard about the project and showed up to help. He hand-cut the tile line completely freehand, which Davis said was incredible to watch.

“When we showed up with Joe, he was like ‘What, tell me about that tile?’” Davis said.

King, impressed by the meticulous dedication, was then fully on board with the skatepark being built on his land. Davis had someone who is a grant writer offer his services and help them write grants to get larger donations from companies. Davis also got community member Bob Lee to help the group set up a nonprofit organization called the Glacier Skate Association.

For Davis, this was more than just building a skatepark. It was about developing a community dedicated to the hard work of making this dream a reality.

“When we did the first huge pour at the Coal Pad, I probably reached out to like 10 of my team riders and was like, ‘You're required to show up and what it'll do for you will change your lives,’” Davis said. “They showed up and sledgehammered, lifted rocks, hauled shit and got dirty. They learned so much. And the people that put their hands on that park, the level of pride that they carry is just, you can't measure it.”

This is what Marc Conner, owner of Contenders Boardshop in Orange, Calif., wanted to do when he started to petition the city to get skateparks built around the Orange County area.

“I wanted to make an impact in the community, and I wanted to make this thing happen,” Conner said. “That's really what it came down to.”

Conner highlighted the importance of having a dedicated community who all share the same goal. This is something the Northwest Skate Collective in Bellingham has done to turn the DIY skatepark under Roeder Avenue into a skatepark.

“It really evolved from the collective that came to the park board and pitched a fairly impressive concept based on successes in other communities to convert the area into a more permanent amenity,” said Nicole Oliver, the city’s Parks and Recreation Department director. “It was very impressive to the park board, and then they made another pitch for a tourism grant for the design, and it started to really gain traction within the city and the administration. And so, it then turned into a priority.”

But for the Coal Pad, building still isn’t done. Davis said they hope to add in a section that gears more towards street skating as well as having easier features for younger kids to learn on, something Davis wants as he has two daughters who skate at the Coal Pad with him and his “Sunday Dad crew” of skaters.

If you want to donate to the Glacier Skate Association or contact them with questions, you can do so through their website.

Bodey Mitchell (he/him) is a campus life reporter for The Front this quarter. He is a second-year Journalism pre-major. In his spare time, Bodey can be found snowboarding or playing guitar. You can reach him at bodeymitchell.thefront@gmail.com.